Piers Courage Derek Bell

THE 1969 SERIES

Although Piers Courage made a great showing in the 1968 Tasman Championship with his Formula 2 McLaren M4A, scoring off each of the eight races and climaxing his tour with a Longford win to finish third for the series, the experts agreed that anyone who meant business in 1969 would need all the engine capacity permitted by the formula. So it was no surprise that the overseas men arrived with 2.5-litre engines and dominated the seven races to occupy the eight uppermost rungs on this year's ladder. The remaining six places were left to New Zealand and Australian residents with four Formula 2 cars, a 2.5 and a 1.5.

Piers Courage

Derek

Bell

As in 1968, Gold Leaf Team Lotus and Ferrari spearheaded the attack, the notable difference being that both parties fielded two-car teams for all races. Lotus drivers were 1968 world champion Graham Hill and the new but highly experienced recruit Jochen Rindt. The Ferrari entry was a quasi-works affair, the two cars having been lent to Chris Amon to manage and run himself, with the Maranello Formula 2 driver Derek Bell for support. Heading the genuine privateers was Englishman Frank Williams, whose first-off Cosworth-Ford V8 powered Brabham was entrusted to Courage.

As usual, Sydney patron Alex Mildren made the scene with his regular driver Frank Gardner. The car was entirely new but powered, as in 1968, by an Alfa Romeo engine. This group contested all seven races.

The only other established international to participate was Jack Brabham, whose original intention was to run at Warwick Farm and Sandown Park. Unloading delays kept him out of the contest at Sydney, but Melbourne provided him with a third place in his 2.5 Brabham-Repco V8.

New Zealand and Australian residents bolstered the fields in their own countries, but in their ranks there were only three bona fide Tasman contenders, each of whom contested six of the seven races. Of the trio, Australian Leo Geoghegan, who did not appear at Teretonga Park, was the most successful with his Repco V8 engined Lotus 39. New Zealanders Graeme Lawrence and Roly Levis (Formula 2 McLaren and Brabham respectively), gave the Australian Grand Prix at Lakeside a miss in favour of the final M.A.N.Z. Gold Star round at Timaru and put their names on the scoreboard with a pair of minor placings apiece in the New Zealand section.

Of the other residents who confined their activities to racing on their home circuits, there were three Australians and one New Zealander, Graham McRae who took sixth spot at Levin in his self-designed and built 1.5 Ford twin-cammer. Mildren increased his stake by entering Kevin Bartlett in a 2.5 Brabham-Alfa V8 and Max Stewart in a Formula 2 Mildren-Alfa and was rewarded with a Warwick Farm fourth and Lakeside sixth, respectively; while Niel Allen took fifth at Lakeside and sixth at Warwick Farm with his Formula 2 McLaren M4A.

1969 Tasman Champion, Chris Amon

(Ferrari).

From the technical viewpoint, most interest was concentrated on the big guns from Europe, although as far as Ferrari and Lotus were concerned there were no novelties. The Ferraris, chassis 0008 for Amon and 0010 for Bell, were basically the standard Formula 2 Dino cars, the V6 engines having a capacity of 2.4 litres and driving through Formula 2 gearboxes fitted with bigger gears. The engines were four-valvers and said to produce a bit more than 300 bhp, although Amon was not convinced. Some 3 inches longer in the wheelbase than Amon's 1968 car, they were about 20 pound lighter. They had nose spoilers and fixed wings located at the engines and roll bars. For the Australian section, mechanic Bruce Wilson devised a variable-angle wing for Amon, electrically operated through a push-button mounted on the steering wheel.

The Lotuses were reputedly new 49Ts, chassis numbered R3 and R5 for Hill and Rindt, with subtle changes in the suspension geometry to reduce camber angles. The Cosworth-Ford DFV V8 engines were said to deliver about 330 bhp and the power was transmitted through ZF gearboxes instead of the more usual Hewlands, although Rindt reverted to the Hewland after Levin in the 49B which replaced his original car written off in that race, and Hill also used the Hewland gearbox from Teretonga onwards. Both cars had the typically wide nose aerofoils and high-riding suspension-mounted wings at the rear which could be feathered for straight-line running by a foot-operated control.

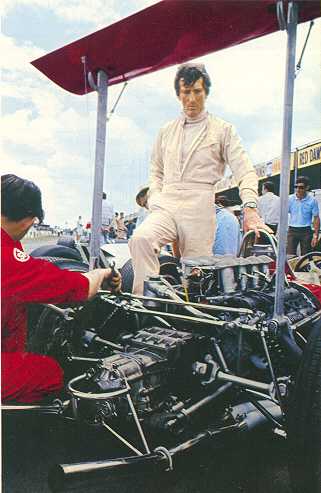

The Frank Williams Brabham was a BT24, chassis number 3, fitted with BT26 suspension. Being the forerunner of the 1969 Brabham Formula I works cars, it was of particular interest with its Cosworth-Ford DFW V8 engine directly attached to the bulkhead behind the cockpit and fitted with an oil radiator mounted well up in the air-stream at the rear. Water pipes were fitted outside the body in Lotus 49 fashion and the car was 21 inches shorter in the wheelbase than a Repco V8-powered BT24. Aerofoil wise, the standard Brabham 'biplane' set-up was used, the rear wing being mounted from the rear suspension uprights.

On of the nicest prepared cars

of the series, Courage's Brabham.

Designed by Len Bailey, Ford of Europe's high-performance engineer whose latest research project is the P69 Ford sports prototype, the Mildren entry was a slimline full monocoque, the engine being mounted in the scalloped rear section with a cross-member over the differential housing providing the rear suspension pick-up points. This car had a long, low nose ducted on top, and high cockpit sides. Finished in Mildren yellow, it was the most distinctive of the Tasman entries. The engine was a bored-out version of the Tipo 33 V8 and had a large rear-mounted oil tank. Drive was through a Hewland FT200 gearbox. It was built with an eye to the future as Bailey designed it to accept the larger Formula A stock-block V8 engines which will come into the Tasman Formula on 1 January 1970.

Geoghegan's not-so-young Lotus 39 was immaculately turned out and was fitted with a twin-cam Repco 840 V8 engine fitted with the 840 heads. The output at 278 bhp was a little down on what the Australian had anticipated, but was well up on that of the Formula 2 cars of Lawrence, Levis and Laurence Brownlie. Lawrence ran the latest version of the McLaren M4A, a car he had built up before his return to New Zealand after his rather disappointing European Formula 2 campaign. Levis and Brownlie were in Brabham BT23Cs, Brownlie's car, organised by Frank Williams, being the one Courage had driven to victory in the final round of the Argentine Temporada.

When Brabham's car appeared at Sandown Park, it was found to be entirely new and designated BT31/1, the chassis being smaller than the BT23 with closely triangulated sections for rigidity, and a detachable cross-member in the engine bay to facilitate plug changes. Cross-flow heads and a lightweight block were features of the Repco sohc-per-bank engine. The recipe was good enough for Brabham to run out 54 of the 55 laps for third behind Amon and Rindt.

National Formula Champion McRae

in his self built McRae-Ford.

Wings, of course, were the 'in thing'. The top performers sprouted them as a matter of course and it was not long before lesser members of the cast were experimenting. Although 'aerofoil' was almost a dirty word by the time the device was banned just before the 1969 Monaco Grand Prix, there is no doubt that during their brief life the wings served a useful purpose. Courage found his Brabham piggish without them during the first day's Pukekohe practice. His dramatic lap time improvements on the second and final day were proof enough of the effectiveness of the Brabham biplanes.

Rindt, who does not care for wings, suffered a handicap at Wigram because he was unable to keep his control pedal depressed and the wing feathered while he was making upward gear changes on the long back straight. The more dexterous Hill was able to keep the wing pedal down and still operate the clutch with his left foot. Rindt, of course, won at Wigram, but Hill's gifted left foot helped him snatch victory in the preliminary heat.At Teretonga, where a year previously 100 mph lap speeds were mere figments of wild imaginations, wings paid the 'ton' bonus, whittling away the vital fractions of seconds on the fast but twisty bits. Even Gardner was impressed by the general handling improvements of the Mildren-Alfa that came with the addition of a pair of minute nose spoilers. And Bell found himself severely handicapped by the loss of one nose spoiler as a result of his start-line bunt with Rindt.

Although he enjoyed enviable success in New Zealand, Amon was hampered by wrongly rated springs. Maranello came to light with the right ones for the Australian section and they helped to clinch the title, but Amon was quick to point out that the electrically adjustable wing devised by Bruce Wilson also played a significant part.

It is worth noting that although the early rounds in this year's Formula I series were marked by an epidemic of wing failures the only sufferer in the Tasman races was Hill whose wing became unstuck in the Australian Grand Prix at Lakeside.

Engines must have been a headache for the Lotus and Williams entries. Changes were frequent throughout the series and since the overhauls were undertaken in England the air freight bill must have been considerable. With Lotus the situation deteriorated to the extent that Mike Costin flew to Sydney to rebuild engines for Hill and Rindt to use in the two final rounds.

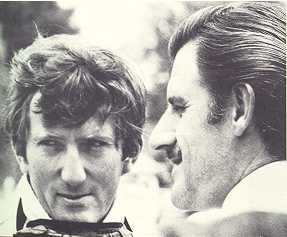

Rindt, who was not a fan of

aerofoils, keeps a close eye on proceedings.

Amon and Bell fared rather better with the Ferraris, although mechanics Bruce Wilson and Roger Bailey had little idle time, for changes were not infrequent. However, only one engine was sent back to Maranello for an overhaul during the series.

An analysis of the results shows that despite the power advantage of the Cosworth-Ford V8 engines, Ferrari reliability was the deciding factor. Front suspension failure put Hill out at Pukekohe and he, Rindt and Courage each had a driveshaft failure, while Rindt had an engine failure in the Australian Grand Prix. The only Ferrari retirement through mechanical trouble was that of Bell at Levin. Amon's first-lap involvement with Courage at Warwick Farm resulted in rear-suspension damage that put him out of the race.

Amon and Bell had six out of seven points-scoring finishes, whereas Rindt, Hill and Courage each scored off only four races. although in two races Courage had accidents, and Rindt did in one. Gardner also scored off four of the seven races. Geoghegan scored off four of his six, while from the same number of starts Levis and Lawrence scored off two.

From three starts Allen gained points from two and Bartlett from one. Stewart started twice and scored once and New Zealander McRae scored once from four starts.

Brabham had a good record, his sole appearance earning him four points for third place. How he would have figured if he had undertaken the full series is anyone's guess.

In the qualifying trials the Cosworth-Ford V8s dominated, Rindt being quickest at Levin, Wigram, Warwick Farm and Sandown Park, and Courage at Teretonga Park. Amon gained pole position for the New Zealand and Australian Grand Prixs. In actual races and preliminaries Amon came out on top with the most fastest laps: the Grand Prixs, Sandown Park and a shared honour with Rindt at Wigram. Rindt was fastest at Levin and Teretonga, and Hill at Warwick Farm in the concluding stages of the race on a drying track and after a long pit stop.

Frank Williams

Jochen and wife Nina

Jochen Rindt and Graham Hill

With Jim Palmer, the most experienced international status driver among the residents, on the sideline for want of a suitable mount, the onus of maintaining New Zealand's local stake in the series fell on the shoulders of Lawrence, Levis and Brownlie, although McRae emerged to provide astonishing support. Well and truly outgunned, Lawrence and Levis made creditable showings. Brownlie, who had been out of racing since his 1968 Grand Prix tangle with Denny Hulme, probably began on the wrong foot for his car did not arrive until the very eve of Pukekohe. Apart from hurried preparation, he lacked time for familiarisation with a Formula 2 car and was unable to give of his best. McRae was the 'find' of the series and showed the tenacity of purpose and technical competence that go to the making of another Amon, McLaren or Hulme.

The other New Zealanders, with their 1.5-litre National Formula cars, the odd Coventry-Climax-engined Tasman model, and the FVA-engined H.C.M. of Frank Radisich, were submerged by the Internationals, although a number of them had the satisfaction of showing the way at one time or another to the English privateer Malcolm Guthrie, who ran a Brabham-Ford twin-cam at Levin, Wigram and Teretonga Park, as well as in the Australian races.

This was Amon's series from start to finish and his success underlined the contention that he must be one of the unluckiest drivers in recent world championship racing. Certainly, when he has a car that is tight and reliable he takes a power of beating. With a Formula I Ferrari as competitive and reliable in its class as was his Tasman car he would be hard to head off from world title honours.

The series marked the end of an era that opened in 1964 with the introduction of the Tasman Formula, for a new formula has been devised for introduction in 1970. While the current 2.5-litre cars remain eligible in the meantime, they will henceforth be joined by the American Formula A or British Formula 5000 cars with their 5-litre stock block V8 engines. The change should add colour to the Tasman scene and introduce new sounds and, it is to be hoped, a wider variety of racing cars and some new faces.

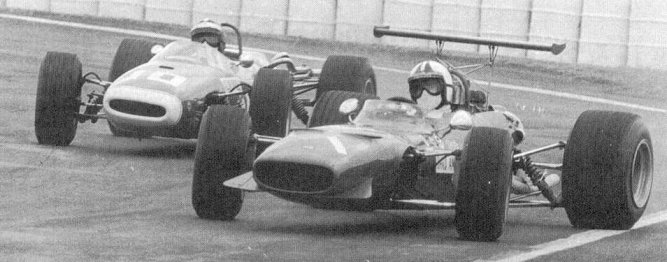

Chris Amon (Ferrari) overtaking

Laurence Brownlie (Brabham).

Patrons at the 29 December meeting at Mount Maunganuiís Bay Park Raceway saw the American Formula A cars in action for the first time in New Zealand and what they saw they liked. The invited American drivers were colourful and quick and many people went away convinced that the big American V8 engines could give the shot in the arm that New Zealand and Australian international races require. McLaren manager Phil Kerr and McLaren driver Denny Hulme forcibly expressed similar views when they holidayed at home over the Christmas-New Year period.

Not all the established manufacturers are producing Formula A/5000 cars, but there should be enough to add variety to the scene, while enterprising New Zealand designers and constructors will no doubt be fielding some of their own confections.

New Zealand would have preferred adoption of the current 3-litre Formula I for the racing category rather than continue the Tasman 2.5 limit, if for no other reason that entrants and constructors not involved in Formula A/5000 would have been able to field race- proved cars without the need for expensive engine modifications. However, the door has been left open for this change and it will be surprising if the 2.5-litre limitation survives beyond 1970.

The other significant development has been the decision of the New Zealand and Australian controlling bodies, as well as international promoters, to dispense with appearance money and expenses in favour of a straight prize money system, the combined pool for which will be around $150,000 dollars next season.

New Zealand will run its usual four Tasman races, but there will also be a non-championship international at Bay Park. In Australia the Tasman races will be at Surfers' Paradise, Warwick Farm and Sandown Park. So there will be eight races and although there will be some variations in the stakes, prize money will be disbursed to the first sixteen runners in each event, those placed between seventh and sixteenth in each race being assured of $400 each, whether they finish or not.

The 1970 Tasman Champion should receive as much in prize money, if not more, than he would have under the old appearance- money arrangement. This new system, which has operated in the United States for many years and is now being adopted in Europe, will put a premium on winning and should make for keen competition, provided always that entrants prepared to take a gamble are forthcoming.

From the local viewpoint it looks attractive. Resident drivers will run knowing that they will almost certainly be recompensed for their efforts and, in fact, should be able to budget on businesslike lines for the first time. The system may well encourage some of the locals to obtain more competitive cars and so lift the general standard of single-seater racing.

From the innovations alone, the Tasman prospects for 1970 appear most exciting.