THE 1968 SERIES

A bonus with this approach was that a proven Formula I chassis could be used without modification or, alternatively, a prototype chassis with a useful Formula I life ahead of it could be built. The only disadvantage might be a weight penalty.

Cost considerations, the scarcity of current Formula I cars and engines, and the fact that, with the exception of Longford, the Tasman circuits are fairly tight and not too fast, made a good power-to-weight ratio in the shape of a Formula 2 car with 1.6-litre engine or, even better, a 2.5-litre engine, also look a reasonably attractive proposition.

Thus it was not surprising that Team Lotus, (which became Gold Leaf Team Lotus from Wigram onwards) and BRM opted for Formula I cars with Tasman-sized engines although, for added insurance, the Bourne team also brought the older stretched V8s. Ferrari, at the party officially for the first time, produced a Formula 2 based car with 2.5-litre engine. Jack Brabham, the constructor-driver, who contested only the Sydney and Melbourne races, used the seemingly all-purpose BT23 chassis and tried three versions of the Tasman Repco V8 engine. Sydney patron Alec Mildren fielded the genuine hybrid, a Brabham BT23D fitted with a 2.5-litre version of the 2-litre Alfa Romeo Tipo 33 V8 engine. Private entrants Denny Hulme, Piers Courage and Jim Palmer, pinned their faith in Cosworth-Ford FVA 1.6-litre engines in appropriate Formula 2 chassis, a Brabham BT23 and in the cases of Courage and Palmer, McLaren M4As. Fields were filled out predominantly by various 1.5-litre Ford twin-cam engines with a sprinkling of Repco V8s and Coventry Climax FPFs in a variety of chassis.

The Gold Leaf Team Lotus cars of Jim Clark and Graham Hill were, in effect, identical with the current Formula I Lotus 49s, but were designated 49T (for Tasman) in deference to the engine size. Hulme's FVA-engined Brabham was the ex-Winkelmann car which in the hands of Jochen Rindt was the fastest Formula 2 machine around last season. It was damaged beyond repair in the New Zealand Grand Prix and was replaced with the ex-works BT23 rolling chassis Hulme used in 1967 Formula 2 races. The M4A McLaren's of Courage and Palmer were ex-works cars, that of Courage being on loan from English racing patron John Coombes.

Designed by Len Terry, the V12 BRMs were originally billed as special Tasman Formula cars. Team manager Tim Parnell dispelled the notion by revealing that the P126 chassis were actually Formula I prototypes. These cars had the bulky Indianapolis look. The rear suspension incorporated two parallel bottom arms and a single top link and radius rods. In its 2.5-litre form the V12 had a rev limit of 10,500, compared with the 3-litre's 10,000. It was probably this variation that led to transistor box and fuel troubles in the final band of 500 rpm. Problems were compounded by the high temperatures generally experienced throughout the series.

Although Englishmen Peter Whitehead and Reg Parnell, along with former New Zealand racing champion Pat Hoare, put Ferrari in the headlines in New Zealand motor racing before the introduction of the Tasman Formula, Enzo Ferrari evinced little if any interest in backing an entry in this part of the world until it became known well on into last year that a factory entry would feature in the Tasman series. There is little doubt that Ferrari's interest was aroused by Chris Amon, his No. 1 driver and a New Zealander who is one of the top Internationals in Formula I and sports-prototype racing. Despite its background the Italian entry was very much a New Zealand car. Built at Maranello by Roger Bailey, it was subsequently air freighted to New Zealand in component form where it was re-assembled in Hunterville by Bruce Wilson. The chassis was more-or-less the same as that of the Formula 2 Dino which made its only European appearance at Rouen last year, with tubes riveted to the monocoque to form a very rigid structure. Based on the familiar and well-proven V6, the engines used in New Zealand had three valves per cylinder, a new fuel-injection system, and were reputed to deliver around 285 bhp from 2.4 litres. For the Australian section, Maranello came up with a four valve per cylinder engine with its Lucas fuel-injection between the banks of the vee rather than between the cams and single rather than dual ignition. Other features of the car were a five-speed Formula I gearbox and Girling disc brakes, mounted inboard at the rear. The engine used in Australia was reputed to develop some 20 bhp more than those used in New Zealand, but it did not prove so reliable.

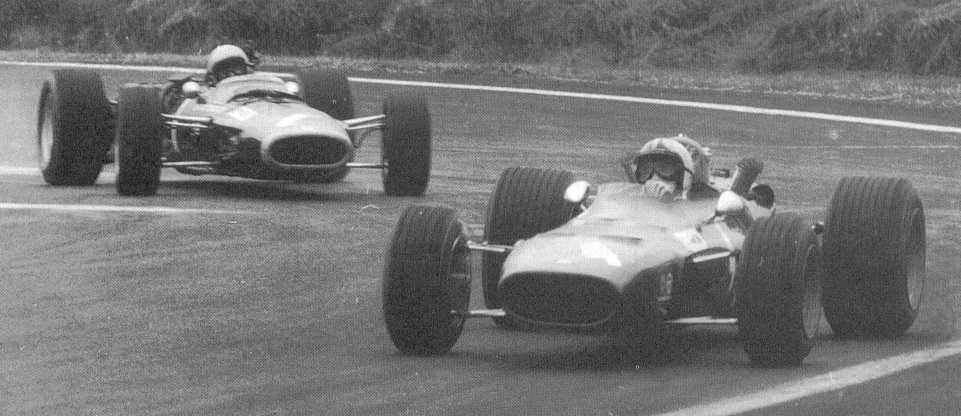

First factory backed Ferrari seen in

New Zealand driven by Amon.

Frank Gardner's Alec Mildren-entered Brabham BT23D with 2464cc Alfa Romeo V8 engine was an extremely well turned out car. The Alfa engine, like that of the three-valve Ferrari, was reputed to push out 285 bhp. Lucas fuel-injection and Marelli ignition were used, along with the ubiquitous Hewland FT200 Formula 2 gearbox.

There is probably some correlation between the method of approach and the measure of success entrants enjoyed. All the same it would not be easy to establish a pattern and one can only reach general conclusions, the first of which is that sheer power and the tremendous ability of Clark earned for Gold Leaf Team Lotus the title, with four wins, a second and a sixth place.

Amon finished runner-up, thanks to resourceful driving and a very good power-to-weight ratio, with two wins, two seconds and two fourths. It remains in the realms of conjecture whether Ferrari's chance of winning the title was negated by the decision to replace the proven three-valve engine with the new four-valve in Australia.

Courage joined the series, a shoestring budget, private entrant with a reputation for letting his heart rule his head. That he won at Longford and was the only driver to score in every race, and so take third uppermost rung on the ladder, might have indicated an emotional readjustment. More likely, the very real challenge of being a driver who had seen the door opened for a place in the BRM team and then abruptly shut before he was given a chance to prove himself provided the needed stimulus. There was also the satisfying knowledge that there were points-scoring ingredients in the FVA engine married to the thoroughly race-worthy McLaren chassis. Courage was the find of the series.

McLaren was the only other driver to win a race and so, to a very limited extent, kept BRM in the picture. That he did manage to get a V12 in the winner's circle at Teretonga was due in the first place to the superhuman efforts of the mechanics who repaired the car after it slithered off the track in the preliminary heat. Then McLaren's steady-does-it approach, when the situation demands it, and his seemingly inherent gift of being able to weigh up a situation and instantly grasp even the most slender advantage that might present itself, paid BRM its only winning dividend.

A New Zealand Grand Prix second place despite a flagging battery was the best Frank Gardner could do for Alec Mildren with the Brabham-Alfa. The following week-end the Australian crashed at Levin, abruptly dispelling a not over-optimistic hope for another good placing, if not a win. Thirds at Teretonga and Longford and a fifth at Sandown Park were the other placings that helped put Gardner fourth equal on the Tasman ladder with Graham Hill. By and large it was not a bad effort, but the team probably did not get right back in step after the Levin disappointment, although the performance of the car satisfied Mildren to the extent that he said he would be entering Gardner in some world title races this year with a Formula I version.

That Hill did not head off Lotus team-mate Clark in Australia led some observers to speculate that the Englishman did not have equal standing and was not the match of Clark in Gold Leaf Team Lotus. The facts are that the drivers enjoyed the same status and it was the points advantage gained by Clark in New Zealand that dictated a supporting role for Hill in Australia. The object of the exercise was a Tasman Championship win for the team rather than for an individual. With two seconds, a third and a sixth, Hill played his part in achieving this objective.

After Gardner and Hill came McLaren on the fifth rung of the ladder with his first plus a sixth at Wigram for his four New Zealand starts. He did not contest the Australian section. The next rung was shared by Hulme and the Mexican BRM driver Pedro Rodriguez. BRM's relatively ineffectual Tasman campaign came in for harsh criticism from people who disregarded the fine record that BRM had built up in previous years. This year's effort, although not successful, could hardly be described as half-hearted in view of the amount of money it had outlaid in bringing such a large team with two brand-new cars as well as the older ones. The V12s certainly were not starting money specials. The record books clearly show that you can't win them all and the odds always lengthen when new cars are introduced, and introduced they must be in one race or another.

Rodriguez, using one of the V8s, scored sixth places at Wigram and Surfers' Paradise and a second at Longford. An amusing side-light was that the Mexican did not realise for some time that the V8, unlike the V12, has a six-speed gearbox! Richard Attwood, who took over McLaren's place in Australia, managed a sixth at Sandown and a fourth at Longford, using the V12.

Hulme's Grand Prix showing proved that he was by no means uncompetitive. He was assured of third place and might well have gained second if he had run out the race. Levin the following week was out on medical grounds. A third in a tremendously fast Wigram race in a hastily-built car was followed by a sixth at Teretonga where a pit stop cost him considerable time. Another sixth followed at Surfers' Paradise and then a fifth at Warwick Farm. A pit stop to tighten a loose spark plug kept him out of contention at Sandown Park, where he finished ninth. He did not start at Longford. Thus he scored in four of the six races in which he started, using in five of them, by force of circumstance, a car which did not have anything like the potential of the one he brought to the Pukekohe starting grid. That be raced at all after the near-tragic Grand Prix crash was tribute enough to his determination and sportsmanship. Others, taking into account the cost involved and the greatly diminished chances of success, might well have been inclined to abandon the series, but not Hulme. That he kept his temper in the face of damaging innuendo and downright rudeness was testimony to his strength of character and good nature. Like the majority of successful people, Denny Hulme has no time for illogical and slipshod thinkers and they were his major critics.

While none of the New Zealand residents campaigned in Australia, the Australian residents were even less prominent on the Tasman points table. Leo Geoghegan took a fourth at Surfers' Paradise with his Lotus-Repco V8 and Kevin Bartlett ran out fifth there in the Alec Mildren 2.5 Brabham-Climax FPF.

New Zealanders at Levin. Yock 10

(Lotus-BRM), Radisich 91 (Lotus 22) and Palmer 41 (McLaren).

Of the seventeen drivers who scored in the series, nine were internationally recognised drivers, while six were New Zealand residents, if Bolton is included, and two were Australian residents.

For the first time since the establishment of the Tasman Formula in 1964 the name of Jack Brabham did not appear on the scoreboard. The former world champion raced only at Sydney and Melbourne and used the BT23E chassis originally built for the Rorstan Racing Team which had hoped to enter Jochen Rindt in the series. Designated the 840, this engine had a magnesium block and lighter crankshaft than the 740 series production Repco engine. To it was mated a Hewland FT200 gearbox and the car was considerably lighter than the BT23A that Brabham used in the 1967 series. However, the engine developed serious oil leaks during practice runs at Warwick Farm and was replaced with a 740 engine for the race. This engine suffered from the same ailment and a long pit stop for oil replenishment cost Brabham all chance. He finished seventh, but did have the satisfaction of setting a new lap record of 1 min 29sec.

For Sandown Park yet another Repco variation was produced. This was the 830 which combined the magnesium block with cylinder heads which had the valves parallel to the cylinder bores and a crossflow induction and exhaust system. This engine proved to be extremely competitive. Brabham made fastest qualifying lap to take pole position and then was mixing it wheel-to-wheel with Amon and Clark when a holed radiator sidelined him after twenty one laps. It seems ironical that the man who has been three times world champion driver, and who has won the Racing Car Constructors' Championship on two occasions, has yet to win the Tasman Championship, especially as he is the man who inspired Repco to design and build an engine specifically for the Tasman Formula.

Finally, it should be mentioned that the tyre war showed no sign of de-escalation, although on this occasion some of the drivers displayed an independence in matter of choice much more noticeable than has been the case in the past. Firestone failed to deliver the necessary goods in time for Pukekohe and contracted drivers Amon and Clark ran on Goodyears and Dunlops respectively. Thereafter they reverted to Firestones, Clark using the latest foot-wide tyres from Teretonga onwards. By the same token, when Goodyear failed to produce at Warwick Farm, Brabham and Gardner switched to Firestones for that race.

Courage, the most consistent performer of the series, used a new type of Dunlop tyre specially developed for Formula 2 racing this year. But his Longford victory was due in part to the Dunlop 970, narrow, round-shouldered tyres which proved most advantageous in wet conditions.

The season provided Firestone with five wins, Goodyear with two and Dunlop one.

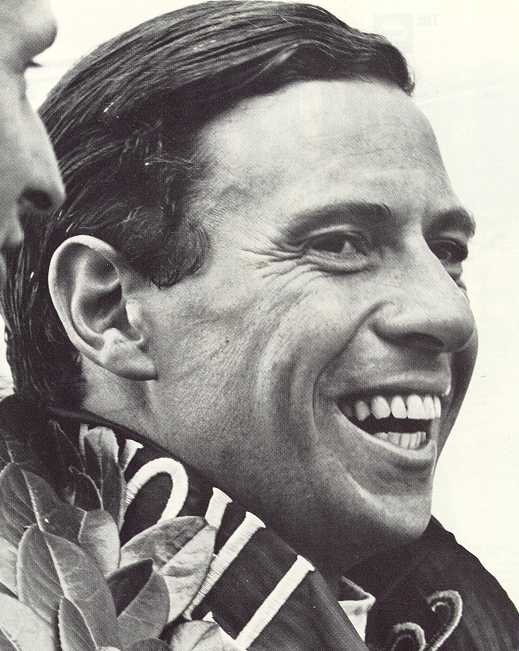

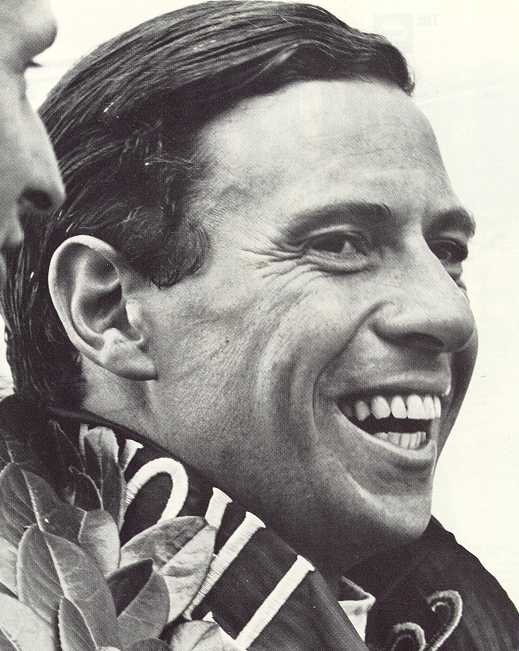

Chris Amon and Bruce

McLaren.

Most would agree that the series was the best to date. There was more variety than usual among the entries and in New Zealand, with the exception of Teretonga where the weather turned sour, crowds were greater than promoters probably anticipated. There is no doubt that the presence of Amon with the works Ferrari and Hulme, New Zealand's first world champion, awakened wider general public interest than has been the case in recent years. But much of the credit was due to Jim Clark, who won his third title and who was one of New Zealand's most popular visitors over the last four seasons. Pukekohe and Longford were the only circuits on which he failed to score Tasman victories. That the Tasman Championship today enjoys such high status is due in no small measure to the part he played in making it internationally known. Motor racing in New Zealand and Australia will never be quite the same without the Flying Scotsman.