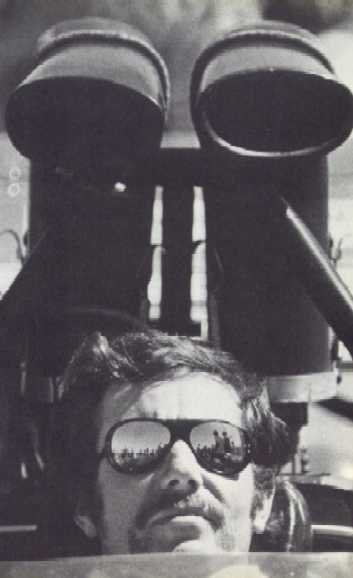

Second time Tasman Champion Graham McRae in the Leda GM1.

THE 1972 SERIES

Second time Tasman Champion Graham McRae in the Leda GM1.

Graham McRae, circuit safety, the tight race schedule, and money were among major talking points during the 1972 Tasman series. From the time McRae wheeled out the Leda GM 1 for NZGP training there were long faces in the opposition camps, which subsequent events did nothing to change. The appalling Pukekohe accident, that claimed Bryan Faloon's life and hospitalised Graeme Lawrence with grievous injuries, sparked debate about circuit safety. Eight races in as many weeks sorely taxed contestants' efforts to remain competitive and, of course, the prize money system was unanimously deemed inadequate by drivers and their connections when they measured it against capital outlay, time and effort involved in mounting a Tasman challenge.

There was nothing said that was really new and it seems safe to assume that the show will be staged again in 1973 although, inevitably, there will be some changes in the cast.

This year, apart from the usual lack of in-depth North American participation, the series was well supported by entrants and their drivers. For the first time since the introduction of the A/5000 formula there were eight events, the last being staged at Adelaide's new International Raceway. Never before in the history of the Tasman Championship, which dates back to 1964, have so many drivers contested all races. Last year, in the seven race series, there were four. This time there were eleven, nine of whom, McRae, Mike Hailwood, Frank Matich, Kevin Bartlett, David Hobbs, Teddy Pilette, Max Stewart, John McCormack and Frank Radisich, scored points. The odd men out were Garrie Cooper and Robbie Francevic.

For the first time Australian designed and built Formula A/5000 cars appeared on the starting grids and for the first time Southland constructor George Begg presented a points scoring car, the Chevrolet powered FM4. McRae, who won the title so convincingly with 39 points to the 28 of Hailwood, 27 of Frank Gardner and 22 of Matich, did so with a car that was the embodiment of his own ideas and largely designed and built by himself.

McRae was a hard man to beat in this series. He won four of the five races in which he finished, Levin, Wigram, Teretonga and Sandown Park, and took fourth place at Warwick Farm.

Teddy Pilette being watched by the large air intakes on his

McLaren.

Frank Gardner won the New Zealand Grand Prix, his race time of 57 min 16.5 sec being 49.5 sec more than Niel Allen's 1971 record. Gardner also made fastest lap in 56.9 sec, 0.2 sec outside Matich's 1971 record. With McRae out after two laps, Gardner was not pushed. Race qualifying times had indicated that, all things being equal, Hailwood would finish 34.8 sec behind Gardner. The margin was 33 sec. For once, theory was borne out in practice.

The weather determined the Teretonga Park result. The more contentious drivers made the wrong tyre choices and came to grief. Bartlett played the game with considerable cool, pressed Pilette into an error and won as he liked. Race and lap times, needless to say, were well outside last year's records, which were set by Allen in the McLaren M10B used this time by Bartlett.

Warwick Farm was Matich's from end to end, with race and lap records into the bargain. This was the race Matich and most others expected Matich to win, so no one was disappointed.

McRae had the series won after Sandown Park, scene of the second Australian Grand Prix to be held within the span of three months. After his three second places in the Australian section Gardner announced his retirement, and Bartlett confessed that he would have preferred to give Adelaide a miss. The race on the new circuit looked pretty open under the circumstances. Hobbs, penalised a minute for allegedly jumping the start, was the winner and must have considered himself lucky, for Hailwood was delayed when his car threw a rear tyre tread. That gave Hobbs the vital time he needed to finish ahead of Hailwood on a countback. McRae, Matich, Bartlett and Stewart retired. No wonder there were some disappointed people about by the time the series ended.

Matich probably had greatest cause for discontent. His Repco V8-engined A50 demonstrated its worth at Warwick Farm and was fastest qualifier for each Australian race. McRae took pole position for Pukekohe, Levin and Wigram. Cassius does not overly concern himself about winning pole position. He considers that there is nothing to be gained by driving a car into the ground before the real competition starts, just for the sake of being fastest qualifier. Hailwood, thanks to the superiority of Firestone's wet weather tyres, was fastest at Teretonga. With Wigram a changed and faster circuit, wet weather qualifying at Teretonga Park, Surfers' Paradise and Warwick Farm, and no basis for comparison at Adelaide, there is not the same foundation for an evaluation of improvements in qualifying times that there was last year. At Pukekohe the top ten drivers' average was 2.32 sec better; at Levin 0.94 sec; and at Sandown Park 1.44 sec.

In greater detail: Allen was fastest NZGP qualifier in 1971 with 56.9 sec; this year McRae went 55.2 for pole and was followed by Gardner (55.6), Hailwood (56.2), Stewart (56.7) and Matich and Lawrence (56.8 each). At Levin. McRae went 43.9, compared with his 1971 pole-winning 44.1, and no other managed to better Cassius's 1971 figure, Matich being closest with 44.2. At Surfers' Matich improved from 68 in 1971 to 66.9 this year, while Gardner (67.3) and McRae (67.6) also improved on the 1971 figure. AIlen's 62.8 sec at Sandown Park in 1971 was bettered by Matich (61.3), McRae and Gardner (61.8 each), Hobbs (62.3) and Bob Muir (62.7), while John McCormack equaled it.

The improvements, generally speaking, were not as good as they were between 1970 and 1971. If a conclusion must be drawn, it would be suggested that the stage has been reached where development might be more profitably directed towards improving handling qualities rather than seeking additional power. This opinion is based on the fact that lap time improvements this year were substantially better on the faster and more open Pukekohe and Sandown Park circuits, rather than on the tighter ones where handling qualities become a more significant factor.

Kevin Bartlett in the ex Niel Allen McLaren M10B.

McRae and Matich, constructors in their own right, have devoted considerable attention to designing good handling cars in the Leda GM1 and Repco Matich A50. Everyone is cagey about disclosing power outputs. Hobbs for example, reckoned that he was giving away as much as 35 bhp to some of the opposition which, he was quoted as saying, had engines producing as much as 515 bhp. McRae claimed that his best Morand engine, running on carburetors like the other two, was giving 488 bhp. If this was so then the handling qualities of the Leda GM 1 played a big part in McRae's success.

Of course, power output remains important. The old Tasman 2.5-litre racing engine, which was admitted to the 1970 and 1971 fields with the A/5000 cars, gave way to 2-litre racing engines in 1972. This was probably in deference to Australia's interest in this size and, no doubt, to help keep the proposed Pacific Championship idea alive. But the decision of the controlling bodies in both countries to give access to 2-litre cars did not impress the realists. Dave McConnell, with his pretty but ineffectual (for Tasman racing) GRD, like Australian and New Zealand residents who helped bolster the fields in their own countries with a variety of four-cylinder Ford-based cars, was never in the hunt. Thirty-seven of the 48 scoring places in the series were filled by Chevy-engined cars and the remaining 11 by the Holden-based Repco V8 (in the Matich A50, Radisich McLaren M10B and the Elfins).

The lack of engine variety is one of the criticisms that have been made against A/5000. The critics, most of whom would like to see, ideally, Formula 1 racing, but would settle for Formula 2, sometimes forget that it is only on comparatively rare occasions that the 12 cylinder motors of Ferrari, BRM and Matra give cause for concern to the owners of Ford's Cosworth V8 in Grand Prix racing. And if it was not for Ford and the various engine specialists who use the Cortina power unit as a basis, Formula 2 would be virtually non-existent. Nevertheless, there is no denying that interest would be added if the A/5000 engine variety was greater. Maybe the venture of English racing car engineer Tony Kitchiner with the Rolls-Royce V8 in Europe this season will add some spice to the A/5000 dish.

But if engine variety was lacking in this series, there was spice enough in the varied makes of A/5000 cars, with examples from Begg, Elfin, Leda, Lola, Matich, McLaren and Surtees all making the scoreboard. McLaren took 18 points scoring places, Surtees 7, Elfin 6, Leda and Lola 5 each, Matich 4 and Begg 3. It must be added that of the 15 points scoring cars, six were McLarens, three were Elfins, two were Lolas and there was one example each of the other makes, Begg, Leda, Matich and Surtees.

Mike Hailwood had to make rapid repairs to the Surtees TS8A

after the Teretonga crash.

McRae's Leda GM 1 was the car that attracted most attention and not merely because, right from the start, McRae looked the Tasman champion for the second successive year. The car is based largely on the experience McRae gained with a McLaren M10A in the 1970 series and the much modified M10B, which incorporated many of his own ideas (and probably some of those of Murray Charles), that carried him to the Tasman title in 1971.

In appearance it has much in common with the new BRM P160 Formula 1 car. It is a strongly-built monocoque, fully stressed with double panels to the top of the body. The Morand Chevy engine is bolted to the rear bulkhead, but it is also supported by a tubular subframe. The engine is mounted very low and so are the laterally located petrol tanks, each with a 15-gallon capacity. They are sited mid-wheelbase so that handling is not markedly affected as the fuel load diminishes. As was the case with the 1971 McRae-modified McLaren M10B, the GM 1 has a gusset between engine and final drive to increase the wheelbase. The GM 1 was fitted with McLaren uprights, hubs and 13in and 15in wheels, although subsequent production versions will be purely Leda or (according to your allegiance) McRae. The GM 1 had outboard disc brakes at the rear. On production versions they are inboard mounted. The discs, incidentally, are of McRae design and are ventilated.

There are two schools of thought about the origins of the Leda GM 1, the first production version of which appeared at this year's London Racing Car Show carrying an LT27 label, signifying that it was the 27th design to come off the drawing-board of Len Terry. Some maintain that the car is Terry's brainchild. Others, backed up by McRae's opinion, say it is definitely a McRae car. Terry converted McRae's sketches into working drawings as McRae, aided by Leda staff, built the car, the working drawings being required before the production version could be laid down. Under the circumstance, it is fair to say that the Leda GM 1I is basically a McRae car. McRae, is of course, an engineer and he has had ten months' experience in a design office. On top of that he has designed and built some other cars, including a sports-racer and the 1500cc New Zealand National Formula winning model of 1969.

Frank Matich (Matich Repco A50).

The Matich A50, designed and built by Sydney racing driver Matich, is also an original design and based on Matich's experience with McLaren Formula 5000 cars, notably the much-modified M10B he raced in the 1971 series. This car is also of monocoque construction, 16-gauge alloy being employed. The shape is rather angular, resembling the Surtees in some respects, and the car has been designed to make maintenance as simple as possible. The stressed Repco V8 engine, for example, can be replaced within a couple of hours while the front and rear suspension have also been designed for easy replacement. This design enabled the car to run in the NZGP with 13in front and 15in rear wheels and then switch to 14in wheels all round for Levin without any dramas. The A50 weighs around 1380lb and has a variable-length wheelbase, ranging from 98in to 103in. The length can be altered quite easily to suit various circuits. Matich is producing the car for sale and already has delivered some examples to the United States. The A50 part of the name, incidentally, denotes that it is a Formula A and that Repco is celebrating its 50th birthday this year.

The McLaren used by Radisich in the series is the ex-Matich car and is much more Matich than it is McLaren. It features the longer wheelbase, achieved by locating the front suspension farther forward than on the normal M10B, also Matich wheels and suspension uprights, and parallel bottom links on the rear suspension instead of the usual McLaren "A" links. Suspension points are revised as well. This car too is powered by the Holden-based Repco V8.

Like the Matich cars, the Elfin MR5s run by constructor Garrie Cooper, John McCormack and Max Stewart (the last a privateer entry) are Repco powered. Based on Cooper's experience building sports cars, the Elfin features a tubular frame with a stressed skin. Suspension is orthodox and the wheelbase is 103in. A Tyrell-type nose section, high-sided cockpit and a partial engine cover are among the car's distinguishing features.

Hailwood was to have brought out the entirely new Surtees TS11 for the series, but two days before it was due to be shipped he piled it up during a test session at Brands Hatch. This was a sad disappointment to Team Surtees, for the new car had shown great promise and in Hailwood's estimation it would have been 2 sec a lap quicker than the cobbled-up car used in the Australian Grand Prix. In the text it is referred to as a TS8A, although it is probably of a more mixed origin, the monocoque section being that of a Formula 1 car. Hailwood demolished the tub when he came to grief in the Teretonga race, but a replacement was flown to Australia in time for the team to build up a new car for the Surfers' Paradise race a week later. The car was something of a bitser but Hailwood got the most out of it and although he did not win a race, he gained two seconds and a third, as well as fourth, fifth and sixth, sufficient points to finish runner-up in the series. On his showing, the Tasman series this year might have been a different story but for that TS11 practice crash.

The ill-fated Rorstan-Porsche of Bryan Faloon.

Like the Hailwood car, the McLaren M22 entered by Kirk F. White and used by Hobbs was also to some extent a bitser. It was really a modified M18, which in turn is a modified M10, the car that Hobbs was quoted as saying was as good as, if not better than, the subsequent models. Because it tended to overheat even under testing in Britain, the M22 was given an additional radiator, side-mounted. Beefed up rear suspension was its other feature.

Evan Noyes, from the United States, had an M18 McLaren, which featured an improved cooling system and some minor suspension and bodywork modifications and ran on Bartz engines. Noyes drove this car without much success in Continental Formula A events in the United States last year and did not have much more joy in the Tasman races. After taking a fourth at Wigram and a fifth at Teretonga Park, he packed up and went home intent upon purchasing a Leda to race in the US this year.

The Team VDS McLaren M10B was the car Pilette used in the 1971 series and was fielded again in original shape. It proved to be exceptionally reliable, the Belgian driver earning the distinction of being the only contender to finish in each of the eight races. His best placing was a second at Teretonga Park, after a protest that he had received outside help to regain the track had been withdrawn.

Teddy Pilette finished every race and scored off six of them to end up seventh

in the Tasman ranking.

Bartlett's M10B was also in original form and just as it was when Allen ran it in the 1971 series. This was Bartlett's first Tasman season as a runner on his own account, in the past he had driven for Alec Mildren. With engines prepared by Sydney's Peter Molloy, he notched a win, two thirds and a fourth, to finish the series on level pegging with Hobbs.

In appearance the Lola T300 was the most dramatic car in the series. It was also the most accident prone. Niel Allen came out of retirement with the intention of driving one for STP in the series but he crashed it in a test session at Surfers' Paradise when the brakes failed. Allen went to hospital with a fractured ankle and shock. The car was rebuilt in time for Bob Muir to use in the first three Australian races, for each of which he was among the fastest qualifiers, although he failed to score.

Lawrence, under JBL sponsorship, could not have been better prepared to make a bid for the title he had won in 1970. To service his car he imported Canadian Tom Anderson to look after the chassis and Lee Muir from the United States to tend the King-modified Chevy engines that had been built up in Michigan. But all came to naught. Lawrence miraculously survived in the crash that claimed the life of Bryan Faloon, but the car was a write-off.

Lawrence was lucky to survive the Pukekohe crash.

Gardner gave the T300 its only win in the series at Pukekohe and the following week damaged it so badly at Levin that he had to forget about the other New Zealand races. He notched seconds in the first three Australian events but was obviously unhappy with his performances and announced his retirement from open-wheeler racing after Sandown Park. His car was raced at Adelaide by Gary Campbell, who managed to finish sixth, after hitting a wall at the new circuit.

There is no doubt that the T300 is an extremely quick car. Gardner was second fastest qualifier at Pukekohe and Surfers' Paradise and third fastest at Warwick Farm and Sandown Park. He used Alan Smith prepared Chevy engines, two of which were fuel-injected, and so did Muir.

The T300 has side-mounted radiators and there is only minimal protection for the driver in front. Lawrence strengthened the front end of his car as soon as he took delivery and the little extra protection probably accounted for his survival. Gardner did similar work when he rebuilt his car in Sydney after the Levin crash.

David Oxton, the Auckland driver, who has quite a number of years of racing experience behind him, has just completed his best season so far, having won the MANZ Road Racing Gold Star and the national Formula Ford Championship. He provided Southland car constructor George Begg with his best season also, for Oxton put a Begg car, the latest FM4, on the Tasman scoreboard for the first time. He was sixth at Levin, fifth at Wigram and third at Teretonga Park. Begg decided that, although the Gold Star had already been won, his first loyalty was to New Zealand and to his sponsor, Winfield. So instead of going to Australia, the Begg team went to Timaru for the South Canterbury Car Club's Gold Star meeting early in February. There Oxton not only won the feature event, but also both heats for the Formula Ford series, the latter with his Winfield-sponsored Elfin.

Graeme McRae at Wigram.

The Begg FM4 is a well-engineered Formula A/5000 car of quite straightforward design, if rather bulky by contemporary standards, and Oxton performed very creditably with it. Begg has built a variety of single-seaters and sports cars over the years that have been raced by various people, including McRae, with considerable success. The appearance of the FM4 on the 1972 Tasman scoreboard establishes Begg as a recognised constructor of a raceworthy Formula A/5000 car and, of course, as New Zealand's leading racing car designer and builder. No doubt more will be heard from the Southland stable in the future.

Just as Oxton did not contest the Australian races, so did a number of Australians race only in their own country. Johnnie Walker drove an Elfin MR5 Repco to fourth place at Adelaide and Warwick Brown scored a fifth with the Pat Burke Racing McLaren M10B at Sandown Park. And, of course, Campbell was sixth at Adelaide in the ex-Gardner Lola T300.

The Tasman series is the one opportunity a year afforded drivers of Formula A/5000 cars to compete against one another. Europe produced its best in the shape of Gardner, the European Formula 5000 champion, and Hailwood, the runner-up. Australia and New Zealand produced their best. But Noyes, the only representative from the United States, and McConnell, the Canadian, would be the first to admit that they are by no means the best Formula A drivers that North America can produce. Hobbs, the 1971 American Formula A champion, freely proclaimed that the competition he encountered was much stronger than he had anticipated. He also said that although John Cannon had been a Formula A champion he was not in the same class as George Follmer, Sam Posey and Mark Donohue. Until American drivers of this calibre can be attracted, the series will not be truly international.

Francevic in the ex-McRae/Radisich McLaren.

Throughout the world these days circuit safety is the concern of everyone connected with motor racing. The Pukekohe tragedy brought this fact home to New Zealanders. It is always easy to be wise after the event and much of the talk that arose from the accident came from sources which, if they had felt any prior concern about safety, had not previously made known their views publicly. Improvements are undoubtedly needed but their nature and extent require both thought and money - perhaps another reason why financial sponsorship of the Tasman series is becoming necessary. If promoters can be relieved of some of the cost involved in presenting good race fields they should be able to divert more income to circuit safety.

Finally, the A/5000 Tasman Formula has had the effect of inaugurating an in-depth motor racing industry in New Zealand and, particularly, in Australia. Locally designed and constructed cars have now proved themselves, as have local engine and tuning specialists.